Norman Dacanay visited South Africa’s Kruger National Park with the aim of seeing what has become known as ‘the Big 5’: lion, elephant, buffalo, rhino and leopard. The park covers nearly 2 million hectares, so he had his work cut out …

[mc4wp_form]

Seeing The Big 5 In Kruger National Park, South Africa’s Largest Game Reserve

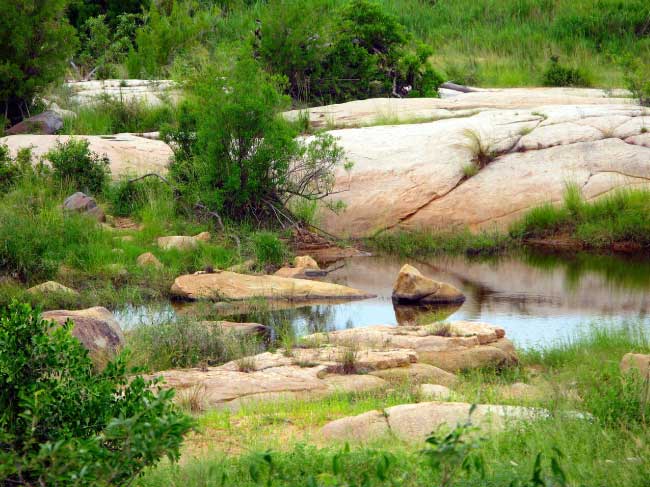

Over four hundred kilometres from the bustling heart of Johannesburg lies Kruger National Park. This protected reserve became South Africa’s first national park in 1926 and is 7,523 square miles in size. Bordered by Mozambique to the east and Zimbabwe to the north, Kruger is part of the massive 36,000 square mile Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park which spans all three countries.

Forty-five minutes outside of the Southern edge of Kruger we met our guide, Israel. A resident of the region and a five-year Park Ranger veteran, Israel could trace his ancestry in the area to a time before any Europeans came to South Africa.

Our photo safari group comprised myself, my wife, a pair of travelling Irish nurses, and a German businessman on a sabbatical. Having greeted our stoic guide we piled on to the back of our vehicle and made our way to the heavily guarded entrance. As we crossed the park’s threshold I couldn’t help but feel as if we were being transported into another world altogether.

It was animals that we had come to see and we were not disappointed. Mere seconds from clearing the guard station we saw zebras and gazelles. We must have taken thirty photos in the first minute alone. The novelty quickly wore off; during the first hour of the safari we had seen hundreds of each of these species.

The First Of The Big 5: Cape Buffalo

Among these grazers was the first of the so called ‘Big 5’; a term coined by early European hunters for the five most difficult and dangerous animals to hunt: the lion, Cape buffalo, African elephant, rhinoceros and leopard.

In my home country of the Philippines I was used to seeing domesticated water buffaloes ploughing the rice fields, and the thought that came into my mind when I saw my first wild Cape buffalo was: That thing looks like a water buffalo, but on a whole lot of steroids! With its heavily-muscled legs and torso, its battering ram-like head and dark coat, it’s no wonder why hunters and locals alike call it “The Black Death”. Responsible for more human deaths per year than any other living creature in Africa, (except perhaps the malaria-spreading mosquito), Cape buffalos are respected and feared throughout the land. But even with their size and ferocity the Cape buffalo is a prey animal. The old, weak and young are targeted by lions.

There is safety in numbers and Cape buffalos not only travel in a herd but also travel in concert with other prey animals such as gazelles and zebras. This is an effective survival strategy: with hundreds of sets of eyes looking out for danger, you’re far more likely to stay alive.

Elephants

As we wound our way through the park I noticed that we were continually having to avoid fallen trees. At first I assumed that they were old trees that had died and fallen, or that strong winds had knocked them down. But then I began to notice that the trees did not seem old. Indeed, their foliage was green and still very much alive. Most of the trees lay perpendicular to the road or track upon which we were travelling.

It was an itch that I just had to scratch, so during a rest stop I asked Israel about them. “Oh that’s the work of the stewards of the forest,” he replied nonchalantly. He went on to explain that “stewards of the forest” was a name given to African elephants, whose presence regulates the environment. In the wild, when certain animals establish a game trail, it is used until it wears down vegetation and creates a depression in the earth. Then, when the rain comes, a stream or creek forms. The banks erode, flooding the surrounding area and killing the grasses and trees in the vicinity.

According to Israel, the elephants prevent this by blocking the game trail before it forms a depression deep enough to start a stream. In the park, the elephants see us as the passing animals and the roads as game trails. The elephants topple the trees onto the road to protect their environment.

We ended up seeing several families of elephants during our stay in Kruger. On one such encounter we startled an adolescent male that was crossing the road with its family ahead of us. Flaring out its ears, the elephant bellowed, took a couple of steps back then charged. Time stood still as each massive footfall brought the animal closer and closer to us. Eventually it stopped, glared at us, and with one last noisy blast from its trunk, wheeled around to re-join its companions.

Afterwards, I asked Israel what would have happened if the elephant really had meant to hit us. His answer was both enlightening and a little worrying. He said that in the event of a real charge the standard procedure is to stop the car! Apparently, moving may have incited the whole herd to charge at us. “But what about the charging elephant?” I asked. “Run!” was his deadpan reply.

According to Israel, the car becomes the target, and the adolescent male could easily have rolled our vehicle. “It is better to be out of the car and be able to run rather than being trapped under the car or worse,” he explained. Yes, I’d be able to run, I thought, but outside the protection of the vehicle … where to? I was glad it never came to that, because some thirty minutes later a deep rumbling noise shook the air and pierced my soul. It was the sound of lions roaring.

Lions

We didn’t get very close. The problem with lions in the wild is that they don’t do much in the day. Lions prefer to expend energy at night or in the early morning when the temperature is cooler and they can use their powerful night vision to catch prey. During the day we would only see them from a distance: resting under a copse of trees or eating a kill from the night before. The nearest we got to them was just under a hundred yards away.

The night brought the lions much closer to us. We could hear them in the darkness outside our tent. Their roars and rumblings filled us with both fear and awe, despite our campground being surrounded by a ten foot high electric fence.

Rhinos

Rhinos are one of the reasons why there is such an emphasis on protection and conservation in Kruger. Throughout the decades, and especially in the recent years, rhinos have been targeted by poachers for their horns.

The first signs we saw of rhinos were their ‘middens’ – large depressions in the dirt upon which they make their beds – which were clearly visible on the grassy landscape. We were fortunate to see several rhinos while at Kruger. To us they seemed nervous; constantly scanning their surroundings with their eyes and ears. On more than a few occasions the rhinos would see us approaching and start moving away.

I felt a great sense of sorrow to know that the lives of these creatures have been forever changed by the greed and irrationality of humans. I was later told by Israel that, despite being under government-funded protection, several of these majestic animals are killed by poachers each year within the borders of Kruger National Park.

Leopard

Ingwe. The word caught my ear and I turned to see Israel talking with another guide, who was pointing further down the dirt road we were on. Israel drove our jeep quickly down the dusty path. It was our last day in Kruger Park and we had been on the road all morning, searching for the most elusive of the Big 5. Ingwe (pronounced eng-weh) is Xhosa for leopard, and we were hopefully now on our way to see one.

Leopards are solitary creatures and tend to hunt at night. Seeing one in the daytime is extremely rare in this part of Kruger, which explains why Israel was in a hurry. If the information turned out to be false, or if the leopard had left the area, we would be leaving Kruger without having seen all of the big five.

Trees on either side of the road were preventing the midday sun from reaching the undergrowth. Israel slowed the vehicle to a crawl and I could see that he was looking intently at something on the ground to our right. He pointed to the spot and whispered “Leopard”. Perfectly camouflaged in the dry, knee-high grass, the big cat could easily have been overlooked. However, surrounding it was a ring of black and grey needles; Israel informed us that it had just eaten a porcupine. It obviously hadn’t been an easy meal: the leopard was now licking its wounds, with several quills still embedded in its muzzle and paws. We admired the creature for several minutes before leaving it to digest its meal in peace. And with our last-minute sighting of the Ingwe, our time in Kruger was at an end. It had taken us right up to the last hour of the last day, but we had seen all of the Big 5.

We left Kruger National Park with incredible memories (and photographs), but something was nagging at the back of my mind. We had devoted so much time to finding the Big 5 that I felt as if we had only seen a fraction of what Kruger had to offer. A look at a map seemed to confirm my fears. Although the overwhelming majority of the park is designated as a refuge and off-limits to tourists, we had still only seen a small part of what was left. There was still so much to see: cheetahs, African hunting dogs, a huge variety of birds, and other megafauna such as kudu and hippos. There will be a next time, I thought to myself. There has to be.

By Norman Dacanay